This review was also published in Sadie Magazine .

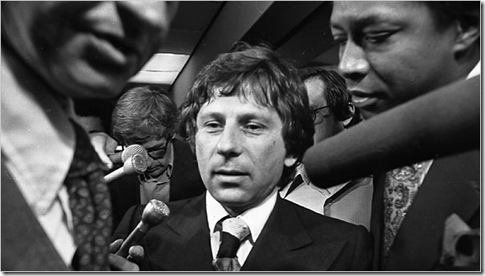

When I was twelve years old, my father introduced me to the work of Roman Polanski by showing me his most heralded film, Chinatown (1974). Though I couldn’t articulate it at the time, I was intensely attracted to the seedy, pessimistic vibe of it all—a vibe I would later come to know as the luminescent pulse that surges through the very flesh of almost every Polanski creation. Upon investigating more of his films and reading his wonderful autobiography, Roman by Polanski, I knew that Polanski, more than any other filmmaker I’d previously known or have known since, was my true cinematic soul mate. We share the same demons, desires, and, most importantly—at the risk of sounding corny—the same knack for survival and perseverance.

These four character traits are also the most common themes running throughout Polanski’s work. Out of the seventeen feature films he has made, nearly all of them present a character—from Oliver Twist (Oliver Twist) to Rosemary Woodhouse (Rosemary's Baby)—who is thrown into a life or death situation and forced to dig him/herself out at any cost. More often than not, this cost becomes the central question for the characters within these narratives. How much does Rosemary want to have a child? How badly does Wladyslaw Szpilman (The Pianist) want to survive, and why? How much is the truth worth to J.J. Gittes (Chinatown)? The questions, like the answers, go on and on.

It’s not terribly puzzling to surmise where these large questions come from. Until recently, Polanski’s life seems to have represented one questionable tragedy after another. As a young lad in Poland, he was left to fend for himself after both of his parents were shipped off to concentration camps. And, after the war was finally over, only his father returned. In 1969, Polanski’s wife, the strikingly beautiful and sweet Sharon Tate, was murdered by the hands of the Manson family.

And, in 1978, Roman Polanski fled to France from the United States to avoid a fifty-year jail sentence for having sexual intercourse with a minor, Samantha (Gailey) Geimer. He had been commissioned by a French fashion magazine to do a photo shoot of young women and hired Ms. Geimer to be one of his models. The sexual act occurred during their second photo session at the home of Jack Nicholson in March of 1977.

The circumstances of the situation still remain mysterious. We now know that champagne and Quaaludes were involved, and that Polanski was charged with six felony crimes. This includes child molestation and sodomy, both of which were eventually pleaded down to a single misdemeanor of unlawful sexual conduct with a minor. Samantha Geimer has gone on the record multiple times since then telling the world that she has forgiven Polanski and that his work should not be impugned because of this one instance in his life. But, the truth is, despite creating a mélange of brilliant films since, like Tess (1979), Bitter Moon (1992), and the painfully unseen Oliver Twist (2005), Polanski’s artistic credibility has diminished in our country’s eyes because of it.

And, due to a thick haze of courtroom drama and mountains of obstructing paperwork, the details of the case were inaccessible to the public eye. This made it very easy for the bulk of the nation to look at this very complex situation with a black and white lens. You can’t sell anything as complex as the truth. It’s much easier to call “child molester” and watch the magazines fly off the rack.

In the recent documentary, Roman Polanski: Wanted and Desired, filmmaker Marina Zenovich explores the netherworlds of this event and reveals that much of the agitation surrounding Polanski’s unique case was caused by the media-hungry Judge Laurence J. Rittenband, then notorious high-profile celebrity trials for his own ends. Though the case never officially went to trial, Rittenband often intentionally fed the media dynamic half-truths in order to both increase his own publicity and cloud the facts surrounding the case. Like a twisted magician, Rittenband created drama where there was none.

For instance, in the midst of the Polanski/Geimer madness, he staged a fake court session with each of the lawyers for the press, even though all of the players already knew the outcome. He was also the first judge to actually hold a press conference in his chambers. Through all this perplexing controversy, Polanski and Geimer reached an amiable plea bargain shortly after the preliminary hearings. The simple truth was that they both wanted to move on. Unfortunately for Polanski, Rittenband didn’t.

Though, initially, Rittenband honored their mutual decision, it wasn’t long before he succumbed to the controversy-starved media and reneged on his word. As Geimer says in the documentary: “Who wouldn’t think about running when facing a fifty-year sentence from a judge who was clearly more interested in his own reputation than a fair judgment or even the well-being of the victim?”

Zenovich not only does an immaculate job of sifting out the dirt of the case, she also does the near impossible: she attempts objective documentary filmmaking. Utilizing interviews with nearly everyone involved, a treasure trove of rare archive footage, and even clips from Polanski’s films, Zenovich accurately and patiently tells both sides of the story while simultaneously maintaining the non-judgmental eye required for such delicate material. She neither victimizes nor demonizes Polanski and Geimer. Instead, she treats her cinematic subjects as people, as living, intelligent beings that deserve to finally have their voices heard and recognized.

By providing this outlet for all of the players (except Polanski himself, as he doesn’t want to drudge up the past) in this epic saga, Zenovich has successfully created a nail-biting account of one of the most public media frenzies of the twentieth century. This documentary is smart and subtle and never relents on telling the whole truth, even if some of the details might make you uncomfortable. Zenovich doesn’t judge, and because of that, she has created one of the best documentaries of the past decade.

**Note** - As of last month, Polanski made the initial motions to get the thirty year old case thrown out of court, citing this documentary as enough evidence to put him in the clear. I love cinema.

When I was twelve years old, my father introduced me to the work of Roman Polanski by showing me his most heralded film, Chinatown (1974). Though I couldn’t articulate it at the time, I was intensely attracted to the seedy, pessimistic vibe of it all—a vibe I would later come to know as the luminescent pulse that surges through the very flesh of almost every Polanski creation. Upon investigating more of his films and reading his wonderful autobiography, Roman by Polanski, I knew that Polanski, more than any other filmmaker I’d previously known or have known since, was my true cinematic soul mate. We share the same demons, desires, and, most importantly—at the risk of sounding corny—the same knack for survival and perseverance.

These four character traits are also the most common themes running throughout Polanski’s work. Out of the seventeen feature films he has made, nearly all of them present a character—from Oliver Twist (Oliver Twist) to Rosemary Woodhouse (Rosemary's Baby)—who is thrown into a life or death situation and forced to dig him/herself out at any cost. More often than not, this cost becomes the central question for the characters within these narratives. How much does Rosemary want to have a child? How badly does Wladyslaw Szpilman (The Pianist) want to survive, and why? How much is the truth worth to J.J. Gittes (Chinatown)? The questions, like the answers, go on and on.

It’s not terribly puzzling to surmise where these large questions come from. Until recently, Polanski’s life seems to have represented one questionable tragedy after another. As a young lad in Poland, he was left to fend for himself after both of his parents were shipped off to concentration camps. And, after the war was finally over, only his father returned. In 1969, Polanski’s wife, the strikingly beautiful and sweet Sharon Tate, was murdered by the hands of the Manson family.

And, in 1978, Roman Polanski fled to France from the United States to avoid a fifty-year jail sentence for having sexual intercourse with a minor, Samantha (Gailey) Geimer. He had been commissioned by a French fashion magazine to do a photo shoot of young women and hired Ms. Geimer to be one of his models. The sexual act occurred during their second photo session at the home of Jack Nicholson in March of 1977.

The circumstances of the situation still remain mysterious. We now know that champagne and Quaaludes were involved, and that Polanski was charged with six felony crimes. This includes child molestation and sodomy, both of which were eventually pleaded down to a single misdemeanor of unlawful sexual conduct with a minor. Samantha Geimer has gone on the record multiple times since then telling the world that she has forgiven Polanski and that his work should not be impugned because of this one instance in his life. But, the truth is, despite creating a mélange of brilliant films since, like Tess (1979), Bitter Moon (1992), and the painfully unseen Oliver Twist (2005), Polanski’s artistic credibility has diminished in our country’s eyes because of it.

And, due to a thick haze of courtroom drama and mountains of obstructing paperwork, the details of the case were inaccessible to the public eye. This made it very easy for the bulk of the nation to look at this very complex situation with a black and white lens. You can’t sell anything as complex as the truth. It’s much easier to call “child molester” and watch the magazines fly off the rack.

In the recent documentary, Roman Polanski: Wanted and Desired, filmmaker Marina Zenovich explores the netherworlds of this event and reveals that much of the agitation surrounding Polanski’s unique case was caused by the media-hungry Judge Laurence J. Rittenband, then notorious high-profile celebrity trials for his own ends. Though the case never officially went to trial, Rittenband often intentionally fed the media dynamic half-truths in order to both increase his own publicity and cloud the facts surrounding the case. Like a twisted magician, Rittenband created drama where there was none.

For instance, in the midst of the Polanski/Geimer madness, he staged a fake court session with each of the lawyers for the press, even though all of the players already knew the outcome. He was also the first judge to actually hold a press conference in his chambers. Through all this perplexing controversy, Polanski and Geimer reached an amiable plea bargain shortly after the preliminary hearings. The simple truth was that they both wanted to move on. Unfortunately for Polanski, Rittenband didn’t.

Though, initially, Rittenband honored their mutual decision, it wasn’t long before he succumbed to the controversy-starved media and reneged on his word. As Geimer says in the documentary: “Who wouldn’t think about running when facing a fifty-year sentence from a judge who was clearly more interested in his own reputation than a fair judgment or even the well-being of the victim?”

Zenovich not only does an immaculate job of sifting out the dirt of the case, she also does the near impossible: she attempts objective documentary filmmaking. Utilizing interviews with nearly everyone involved, a treasure trove of rare archive footage, and even clips from Polanski’s films, Zenovich accurately and patiently tells both sides of the story while simultaneously maintaining the non-judgmental eye required for such delicate material. She neither victimizes nor demonizes Polanski and Geimer. Instead, she treats her cinematic subjects as people, as living, intelligent beings that deserve to finally have their voices heard and recognized.

By providing this outlet for all of the players (except Polanski himself, as he doesn’t want to drudge up the past) in this epic saga, Zenovich has successfully created a nail-biting account of one of the most public media frenzies of the twentieth century. This documentary is smart and subtle and never relents on telling the whole truth, even if some of the details might make you uncomfortable. Zenovich doesn’t judge, and because of that, she has created one of the best documentaries of the past decade.

**Note** - As of last month, Polanski made the initial motions to get the thirty year old case thrown out of court, citing this documentary as enough evidence to put him in the clear. I love cinema.

No comments:

Post a Comment